Overview

We recently finished a stream series where we wrote a static unpacker and deobfuscation scripts for 64-bit Qakbot samples using Binary Ninja. Binary Ninja is a powerhouse reverse engineering suite that provides a plethora of functionality that is useful when reverse engineering malware. It has a robust Python API for interacting with abstractions (semantic representations) generated by their multiple levels of Binary Ninja Intermediate Languages (BNILs). These abstractions result in large simplifications of disassembled instructions into intrinsic functions and high level languages that can be accessed directly and easily, which we leveraged multiple times throughout these streams.

Seamless Headless Experience

Binary Ninja commercial versions provide the ability to run in headless mode, which we worked with throughout these streams. We have yet to see a reverse engineering suite that can provide such a seamless headless experience as Binary Ninja:

bv = BinaryViewType['PE'].open(<Path>)

bv.update_analysis_and_wait()

These two lines will load and process the entire provided binary producing a Binary Ninja database that can be used to access all levels of BNILs from the BinaryView.

Sidekick

What’s a 2024 blog without talking about AI? Vector35 has released a plugin named Binary Ninja Sidekick which integrates multiple large language models directly within the UI that can be interacted with to assist with database markups, ask questions and generate automation scripts for you. The models have contextual awareness of the database which can be leveraged to produce automation based on the content itself, rather than abstract asks like you would do with other LLM chat interfaces or development environments. We’ve seen multiple open source projects that have attempted to achieve the same seamless interaction with LLMs, but this is the best that we’ve observed thus far. We experimented with Sidekick in the third part of our stream series to recover structures, automatically translate High Level Intermediate Language (HLIL) into Python code, and identify encoding algorithms.

Obfuscation Techniques

The Qakbot samples we analyzed contain the following obfuscation techniques that we addressed throughout these streams:

- Stack strings

- Multiple levels of packers resulting in a final Qakbot DLL

- Dynamic function resolution using function hash tables

- Encrypted string tables

The methods in which all of these obfuscation techniques are addressed using Binary Ninja with the help of other projects will be described throughout this post.

Stack Strings

The stack strings encountered were no match for Binary Ninja’s HLIL. The following disassembly contains a stack string that is used as an XOR key to decrypt a first-stage shellcode segment:

691bc02b c644247040 mov byte [rsp+0x70 {copied_alphabet}], 0x40

691bc030 c644247141 mov byte [rsp+0x71 {var_147}], 0x41

691bc035 c64424726c mov byte [rsp+0x72 {var_146}], 0x6c

691bc03a c64424737a mov byte [rsp+0x73 {var_145}], 0x7a

These instructions (truncated for readability) are simplified into the HLIL instruction:

__builtin_strncpy(dest: &copied_alphabet, src: "@AlzsQ1DSS...", n: 0x3a)

Making it easy for us to extract the XOR key passed as a parameter to __builtin_strncpy.

Static Unpacker

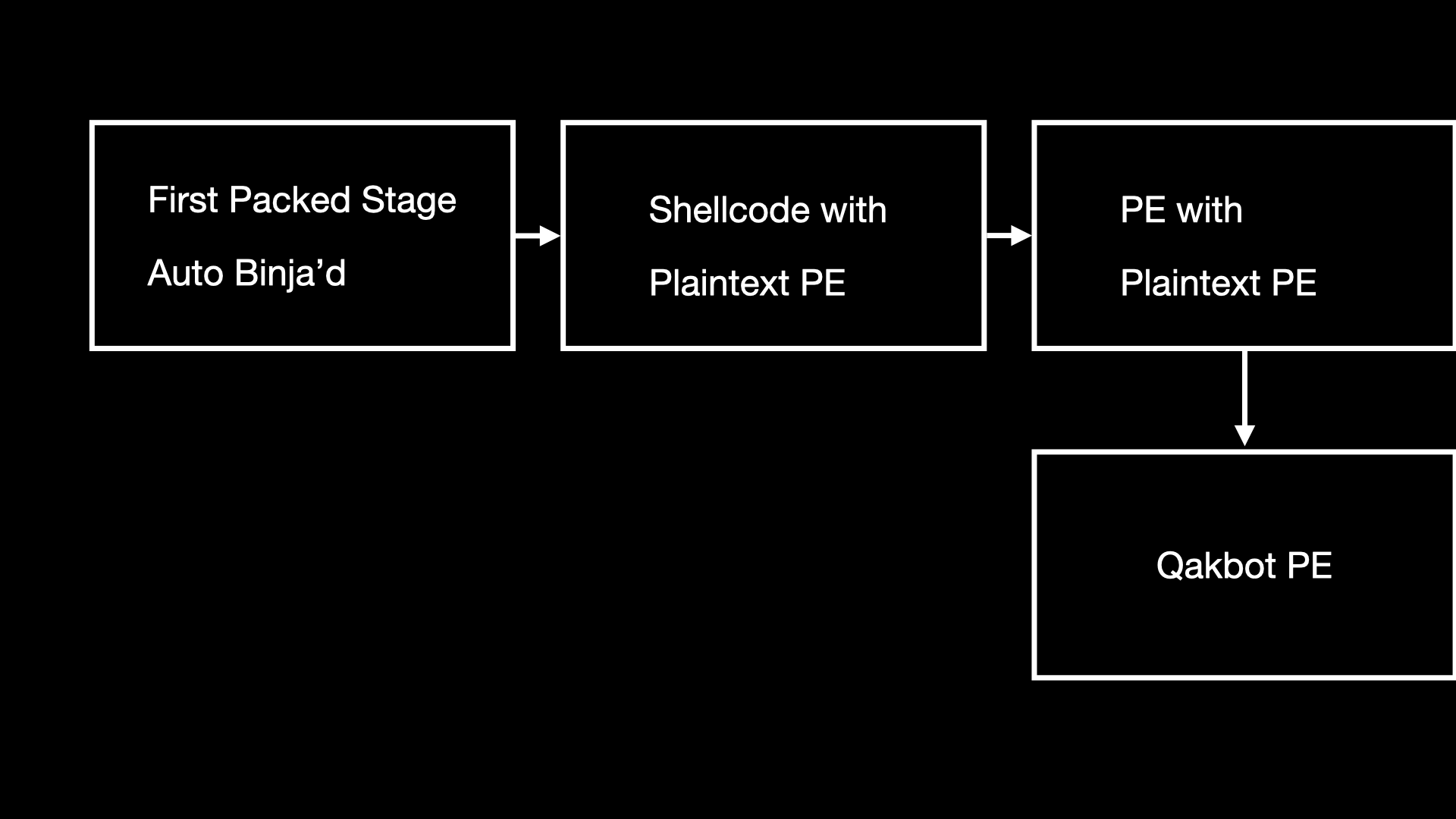

The packer that we encountered contains multiple stages, these are depicted in the following diagram:

Our goal was to unpack every step within this diagram statically using Binary Ninja scripting where possible, and extract a final Qakbot binary for analysis. The final script can be found here.

The first stage of this packer extracts position independent shellcode ciphtertext from an embedded PE resource using Windows resource APIs, decrypts this shellcode using the XOR key mentioned in the previous section, and executes the shellcode in memory. In order for us to automatically extract this resource and decrypt it, we needed to process the binary using Binary Ninja and leverage the Binary Ninja Python API to extract needed attributes.

Generic Function Identification

First, we needed a method of generically identifying the location of these attributes within the database HLIL. In this case, we only needed to identify a single function, which contains both a reference to the resource identifier that maps to the resource, and the XOR key to decrypt the ciphertext. The Binary Ninja Python API contains a function called binaryninja.highlevelil.HighLevelILFunction.visit which allows recursive enumeration of HLIL instructions. This is the best approach (over iteration) as HLIL instructions are often nested within (tree) structures. We can use visit to find the target __builtin_strncpy intrinsic function:

def get_key(bv):

print("Looking for decryption key...")

key = None

for inst in bv.hlil_instructions:

inst.visit(visitor)

return key

def visitor(_a, inst, _c, _d) -> bool:

if isinstance(inst, commonil.Localcall):

if len(inst.params) > 1:

if inst.tokens[0].text == '__builtin_strncpy':

print("Found target strncpy: {}".format(inst))

key = bytes(inst.params[1].tokens[1].text + "\x00", 'ascii')

We then call isinstance to identify if the instruction in question is of type commonil.Localcall (the IL object for calls) and that the instruction contains the token text of __builtin_strncpy. Once verified, the XOR key is extracted using key = bytes(inst.params[1].tokens[1].text + "\x00", 'ascii'). Another strength of the Binary Ninja API is the ability to “work backwards” from an instruction object, which we use to acquire the resource identifier in this function:

rsrc_inst_index = 4

rsrcid = None

rsrc_inst = list(inst.function.instructions)[rsrc_inst_index]

rsrcid = rsrc_inst.operands[1].value.value

Here we knew each resource identifier would be at the 4th instruction (from looking at multiple samples) within each HLIL representation of the target function (a weak heuristic but works nonetheless). Therefore, we acquire all HLIL instructions for the function using inst.function.instructions, and extract the resource identifier value from the instruction’s operand at this index using rsrc_inst.operands[1].value.value.

Using the extracted resource identifier, we can extract the resource data using PEFile to enumerate the PE resource directories:

def extract_resource(fpath, min_resource_size, rsrcid):

rsrc_data = None

pe = pefile.PE(fpath)

pe_mapped = pe.get_memory_mapped_image()

for rsrc in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_RESOURCE.entries:

for entry in rsrc.directory.entries:

if entry.directory.entries[0].data.struct.Size >= min_resource_size and entry.struct.Name == rsrcid:

rsrc_offset = entry.directory.entries[0].data.struct.OffsetToData

rsrc_size = entry.directory.entries[0].data.struct.Size

rsrc_data = pe_mapped[rsrc_offset:rsrc_offset + rsrc_size]

return rsrc_data

The XOR key is then used to decrypt the resource data:

def xor(key, ct):

r = bytes()

for i, b in enumerate(ct):

r += (b ^ key[i % len(key)]).to_bytes(1, 'little')

return r

Extracting Plaintext PEs

Fortunately, all later stage portable executables are plaintext within the infection chain, therefore, we can simply carve all subsequent plaintext PEs within the decrypted shellcode blob. The only difficulty is acquiring the exact size of the PEs, which requires parsing their optional headers for sections and adding all physical section sizes together to acquire their total size as they’d reside on disk. Fortunately, there’s the amazing Binary Refinery project by our friend Jesko that contains a “unit” that will do exactly this: carve_pe. We ended up using code from the project and the get_pe_size function to carve out multiple PEs from the plaintext shellcode segment:

# Based on https://binref.github.io/units/pattern/carve_pe.html

# Thanks Rattle <3

def carve_pe(data):

cursor = 0

mv = memoryview(data)

carved = []

while True:

offset = data.find(B'MZ', cursor)

if offset < cursor: break

cursor = offset + 2

ntoffset = mv[offset + 0x3C:offset + 0x3E]

if len(ntoffset) < 2:

return None

ntoffset, = unpack('H', ntoffset)

if mv[offset + ntoffset:offset + ntoffset + 2] != B'PE':

print(F'invalid NT header signature for candidate at 0x{offset:08X}')

continue

try:

pe = PE(data=data[offset:], fast_load=True)

print("Found a valid PE: {}".format(bytes(data[offset:offset+256]).hex()))

except PEFormatError as err:

print(F'parsing of PE header at 0x{offset:08X} failed:', err)

continue

pesize = get_pe_size(pe, memdump=False)

pedata = mv[offset:offset + pesize]

carved.append(bytes(pedata))

return carved

This results in the following output:

$ python3 extract_qakbot.py qakbot-64-bit/dll/780be7a70ce3567ef268f6c768fc5a3d2510310c603bf481ebffd65e4fe95ff3 2> /dev/null

Looking for decryption key...

Found target strncpy: __builtin_strncpy(&var_148, "@AlzsQ1DSS...", 0x3a)

Identified key: b'@AlzsQ1DSS...' // Identified Resource ID: 948

Found a valid PE: 4d5a9

invalid NT header signature for candidate at 0x00001AC6

Found a valid PE: 4d5a9

The second PE is the Qakbot DLL that is written to disk by the script for further analysis.

Dynamic Function Resolution

The Qakbot DLL performs dynamic function resolution using a series of hash tables. In the sample that we analyzed, the dynamic function resolution is performed in two steps:

- Decrypt given DLL ciphertext using a hard-coded XOR key (

0xa235cb91) - The resulting DLL’s export table is then walked to resolve a provided hash table, which contains a series of CRC32 hashes modified with a single XOR operation that map to Windows API functions

The resulting API functions are then stored within a function table whose first address is stored within a global variable. These steps are performed for multiple function tables and the resulting global variables are used to access functions through relative offsets within these tables throughout the binary.

In order for us to recover the function tables used throughout the binary, we wrote automation to perform the following:

- Decrypt each DLL name

- Parse each DLL export table to extract all possible function names

- Hash each export and compare them to each hash table entry

- Write discovered function names into a format that can be consumed by Binary Ninja

Extracting Calls to Dynamic Function Resolution Function

Given that each hash table was resolved by the same function, we were able to extract all calls to this function in order to extract each hash table and their respective DLL names:

def resolve_hash_tables(bv, module_ct_bytes, xor_key_bytes, hash_xor, import_res_addr):

resolved_hashes = {}

import_resolution_func = bv.get_function_at(import_res_addr)

for call_site in import_resolution_func.caller_sites:

tokens = call_site.hlil.tokens

hash_table_addr = tokens[3].value

offset = tokens[7].value

#This shift is done in the code

hash_table_size = (tokens[5].value >> 3) * 4

Cross-references to our hash table resolution function are acquired using import_resolution_func.caller_sites and all parameters for the specific function call are acquired using the tokens for the call using call_site.hlil.tokens.

Recovering DLL Names

Each DLL ciphertext is stored within a buffer that we’ve named module_ct_bytes. Each ciphertext segment is stored at a relative offset that is passed within the offset parameter. The length of the encrypted DLL name is stored within a BYTE value at this offset, which is followed by the ciphertext in the format of:

struct enc_module_info {

BYTE module_name_length;

BYTE module_name_ct[];

};

Here we use these values to extract the ciphertext at each offset within module_ct_bytes and decrypt them using a 4-byte XOR key:

def decrypt_mod_name(module_ct_bytes, offset, xor_key):

offset_mod = offset * 0x21

module_name_length = module_ct_bytes[offset_mod]

module_name_ct = module_ct_bytes[offset_mod+1:offset_mod+1+module_name_length]

rbytes = bytes()

xoff = 0

for i, b in enumerate(module_name_ct):

rbytes += (b ^ xor_key[i & 3]).to_bytes(1, byteorder='little')

return rbytes.decode('ascii')

Hashing Export Functions with Binary Ninja

The Export functions of each DLL dependency can be acquired by opening each DLL with Binary Ninja headlessly and extracting the export symbols for each DLL:

def gen_dll_hash_table(dllname, hash_xor):

#print("Export functions for DLL: %s" % dllname)

dbv = BinaryViewType['PE'].open("dependencies/{}".format(dllname))

table = {}

for symbol in dbv.get_symbols_of_type(SymbolType.FunctionSymbol):

if symbol.binding is SymbolBinding.GlobalBinding or symbol.binding is SymbolBinding.WeakBinding:

tmp_symbol = re.sub("Stub", "", symbol.full_name)

rhash = zlib.crc32(bytes(tmp_symbol, 'ascii')) ^ hash_xor

table[rhash] = tmp_symbol

return table

In order to acquire the needed DLLs, we simply decrypted all required DLL names first and then copied them into the dependencies directory on our development machine. Each export name is hashed using CRC32 and XORed with the hard-coded XOR key. Each result is stored within a hash table for comparison against the hash tables extracted from the Qakbot DLL.

Structure Generation and Relative Pointer Markups in Binary Ninja

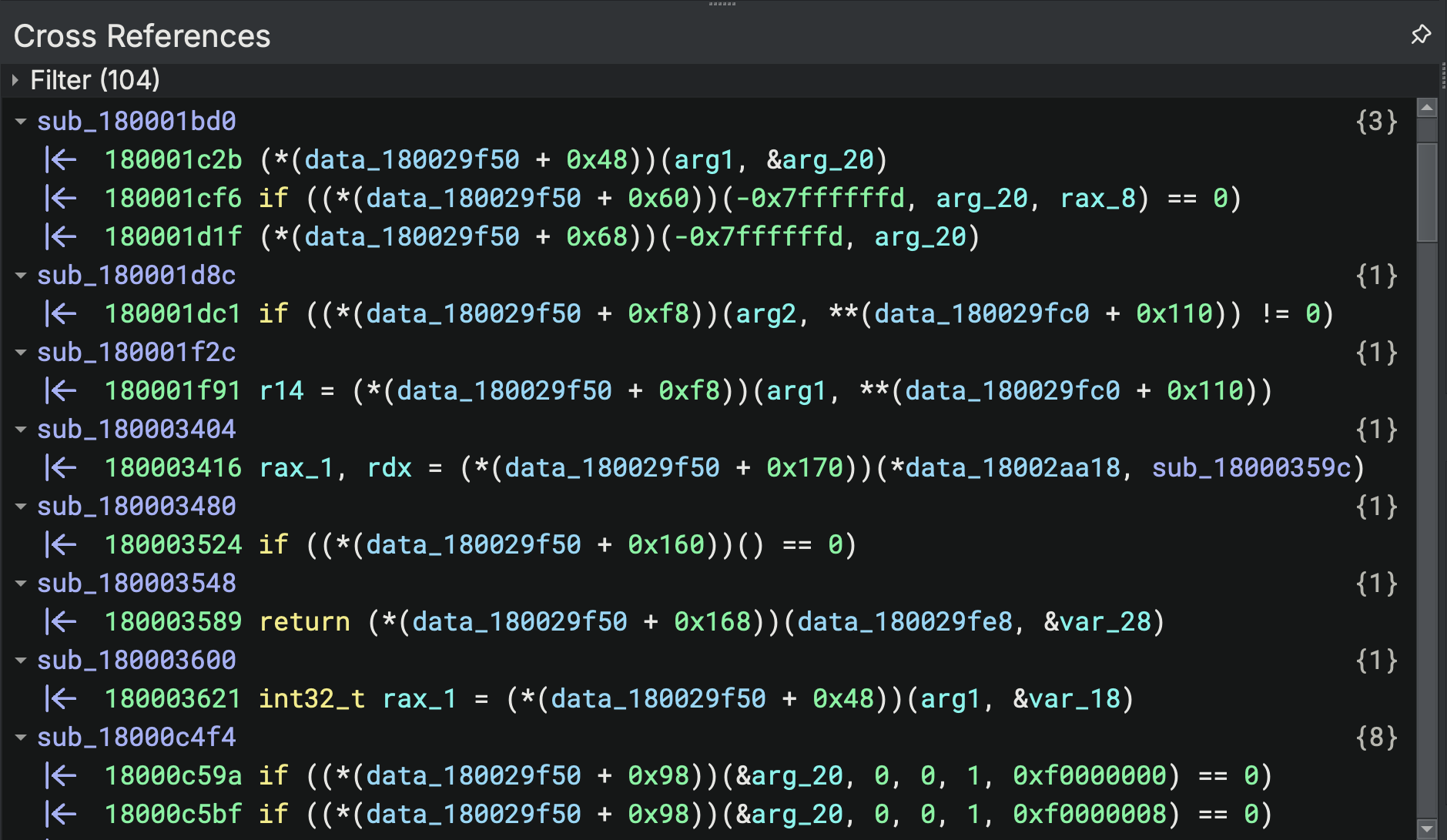

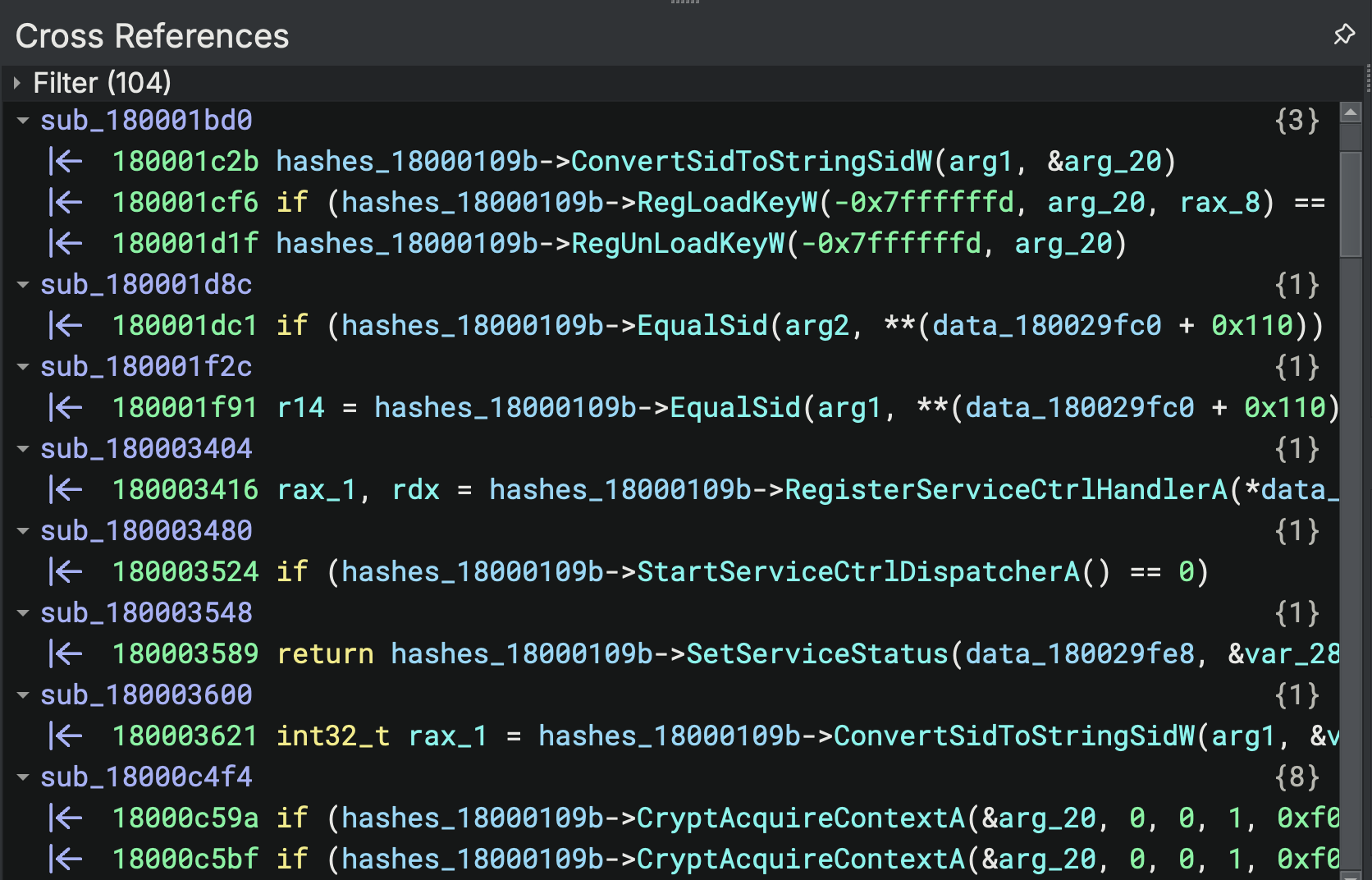

Calls to relative offsets within each dynamically resolved function table can be seen throughout the Binary Ninja database:

In order for us to mark these relative offsets with resolved function names, we need to create structures that label these relative offsets as these resolved functions:

hash_table = bv.read(hash_table_addr, hash_table_size)

hash_table_hashes = struct.unpack("I"*(hash_table_size//4), hash_table)

dll_hash_table = gen_dll_hash_table(dllname, hash_xor)

for chash in hash_table_hashes:

if chash in dll_hash_table:

found_func_name = dll_hash_table[chash]

else:

found_func_name = "unk_%x" % chash

if found_func_name:

resolved_hashes[found_func_name] = chash

print(generate_header(resolved_hashes, call_site.address))

First, we read the hash table in its entirety using bv.read using the function parameters acquired earlier, then struct.unpack these into INT32 values to compare to our dynamically generated hash tables. Each discovered hash is set into a resolved_hashes dictionary, which is then passed to a struct generation function:

def generate_header(resolved_hashes, hash_table_addr):

rstr = bytes()

rstr += b"struct hashes_%x {" % hash_table_addr

for k, v in resolved_hashes.items():

rstr += bytes("int64_t {}; ".format(k, v), 'ascii')

rstr += b"};"

return rstr.decode('ascii')

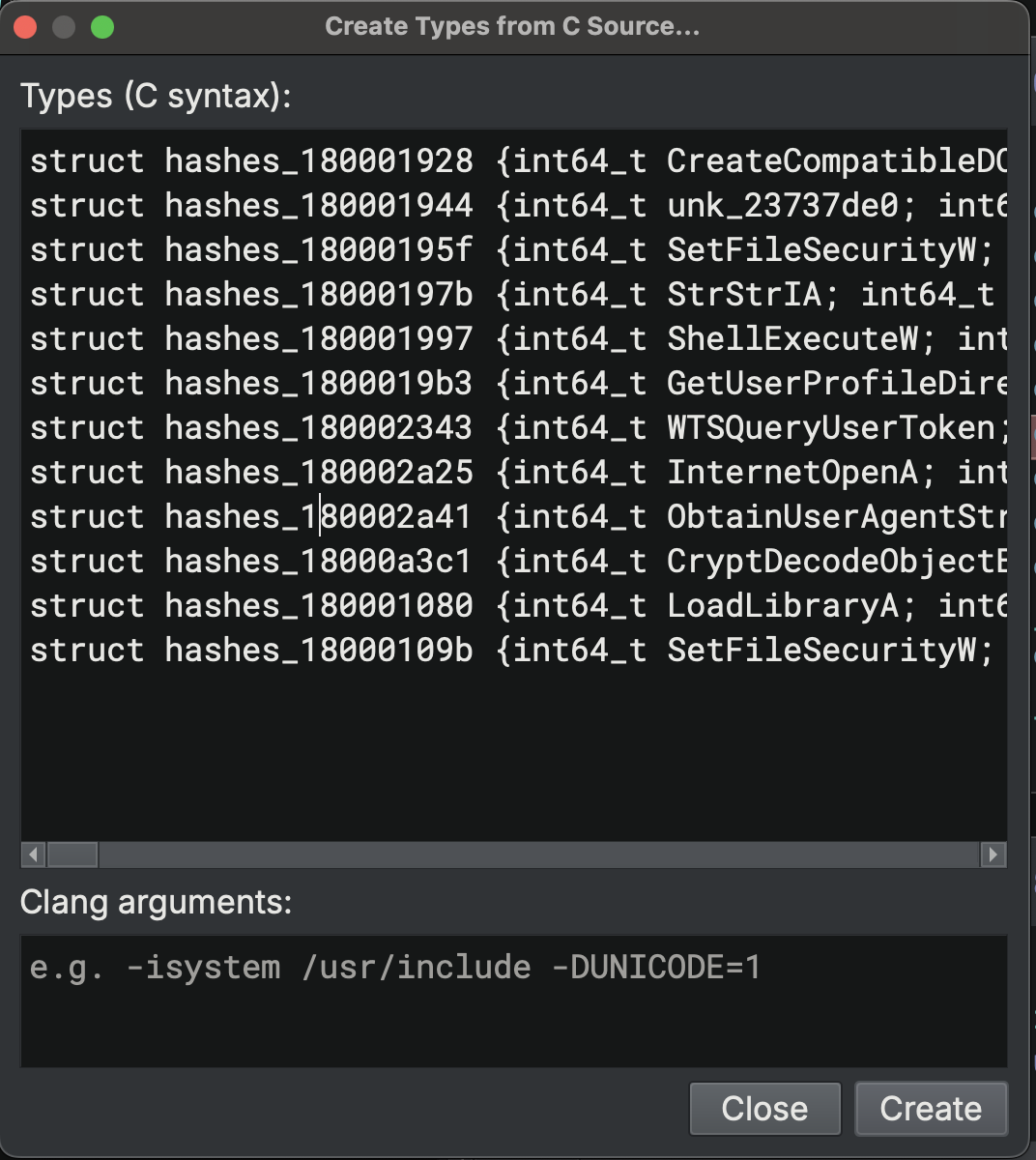

This creates a struct definition with each int64_t member being the name of each resolved API function name. This results in the following output of C structures:

struct hashes_1800018d2 {int64_t LoadLibraryA; int64_t LoadLibraryW; int64_t FreeLibrary; int64_t GetProcAddress; int64_t GetModuleHandleA; int64_t GetModuleHandleW; int64_t CreateToolhelp32Snapshot; int64_t Module32First; int64_t Module32Next; int64_t WriteProcessMemory; int64_t OpenProcess; int64_t VirtualFreeEx; int64_t WaitForSingleObject; int64_t CloseHandle; int64_t LocalFree; int64_t CreateProcessW; int64_t ReadProcessMemory; int64_t Process32First; int64_t Process32Next; int64_t Process32FirstW; int64_t Process32NextW; int64_t CreateProcessAsUserW; int64_t VirtualAllocEx; int64_t VirtualAlloc; int64_t VirtualFree; int64_t OpenThread; int64_t Wow64DisableWow64FsRedirection; int64_t Wow64EnableWow64FsRedirection; int64_t GetVolumeInformationW; int64_t IsWow64Process; int64_t CreateThread; int64_t CreateFileW; int64_t CreateFileA; int64_t FindClose; int64_t GetFileAttributesW; int64_t SetFilePointer; int64_t WriteFile; int64_t ReadFile; int64_t CreateMutexA; int64_t ReleaseMutex; int64_t FindResourceA; int64_t FindResourceW; int64_t SizeofResource; int64_t LoadResource; int64_t GetTickCount64; int64_t ExpandEnvironmentStringsW; int64_t GetThreadContext; int64_t SetLastError; int64_t GetComputerNameW; int64_t Sleep; int64_t SleepEx; int64_t OpenEventA; int64_t SetEvent; int64_t CreateEventA; int64_t TerminateThread; int64_t QueryFullProcessImageNameW; int64_t CreateNamedPipeA; int64_t ConnectNamedPipe; int64_t GetLocalTime; int64_t ExitProcess; int64_t GetEnvironmentVariableW; int64_t GetExitCodeThread; int64_t GetFileSize; int64_t VirtualProtect; int64_t VirtualProtectEx; int64_t unk_4996c616; int64_t CreateRemoteThread; int64_t SetEnvironmentVariableW; int64_t ResumeThread; int64_t TerminateProcess; int64_t unk_33439cf0; int64_t DeleteFileW; int64_t CopyFileW; int64_t AllocConsole; int64_t SetConsoleCtrlHandler; int64_t GetModuleFileNameW; int64_t GetCurrentProcess; int64_t CreatePipe; int64_t GetExitCodeProcess; int64_t GetCommandLineW; int64_t DuplicateHandle; };

struct hashes_1800018ee {int64_t NtAllocateVirtualMemory; int64_t NtFreeVirtualMemory; int64_t RtlAllocateHeap; int64_t RtlFreeHeap; int64_t RtlGetVersion; int64_t NtCreateSection; int64_t NtUnmapViewOfSection; int64_t NtMapViewOfSection; int64_t NtWriteVirtualMemory; int64_t NtProtectVirtualMemory; int64_t NtClose; int64_t ZwQueryInformationThread; int64_t RtlInitUnicodeString; int64_t RtlCreateProcessParametersEx; int64_t NtQueryInformationProcess; int64_t NtResumeThread; };

struct hashes_18000190c {int64_t MessageBoxA; int64_t EnumWindows; int64_t RegisterClassExA; int64_t CreateWindowExA; int64_t ChangeWindowMessageFilter; int64_t ShowWindow; int64_t UpdateWindow; int64_t GetMessageA; int64_t TranslateMessage; int64_t DispatchMessageA; int64_t DestroyWindow; int64_t UnregisterClassA; int64_t PostQuitMessage; int64_t unk_dd231aa5; int64_t GetKeyboardLayoutList; int64_t GetSystemMetrics; int64_t GetProcessWindowStation; int64_t GetUserObjectInformationW; int64_t CharUpperBuffW; int64_t CharUpperBuffA; int64_t GetClassNameA; int64_t GetForegroundWindow; int64_t GetDC; int64_t GetCursorInfo; int64_t CopyIcon; int64_t GetIconInfo; int64_t DrawIconEx; };

struct hashes_180001928 {int64_t CreateCompatibleDC; int64_t GetDeviceCaps; int64_t CreateCompatibleBitmap; int64_t SelectObject; int64_t BitBlt; int64_t GetObjectW; int64_t GetDIBits; int64_t DeleteDC; int64_t DeleteObject; };

struct hashes_180001944 {int64_t unk_23737de0; int64_t unk_43a8d158; int64_t NetWkstaGetInfo; int64_t unk_642a3b8c; int64_t unk_b0832666; int64_t unk_7d528939; };

struct hashes_18000195f {int64_t SetFileSecurityW; int64_t AdjustTokenPrivileges; int64_t SetEntriesInAclA; int64_t AllocateAndInitializeSid; int64_t FreeSid; int64_t RegOpenKeyExA; int64_t RegQueryValueExA; int64_t RegCloseKey; int64_t ConvertSidToStringSidA; int64_t ConvertSidToStringSidW; int64_t RegCreateKeyA; int64_t RegSetValueExA; int64_t RegLoadKeyW; int64_t RegUnLoadKeyW; int64_t OpenSCManagerW; int64_t CreateServiceW; int64_t StartServiceW; int64_t DeleteService; int64_t CloseServiceHandle; int64_t CryptAcquireContextA; int64_t CryptCreateHash; int64_t CryptHashData; int64_t CryptVerifySignatureA; int64_t CryptReleaseContext; int64_t CryptDestroyKey; int64_t CryptDestroyHash; int64_t CryptDeriveKey; int64_t CryptSetKeyParam; int64_t CryptEncrypt; int64_t CryptDecrypt; int64_t CryptGetHashParam; int64_t EqualSid; int64_t LookupAccountSidW; int64_t OpenProcessToken; int64_t GetTokenInformation; int64_t OpenThreadToken; int64_t GetSidSubAuthorityCount; int64_t GetSidSubAuthority; int64_t ConvertStringSecurityDescriptorToSecurityDescriptorW; int64_t GetSecurityDescriptorSacl; int64_t SetSecurityInfo; int64_t InitializeSecurityDescriptor; int64_t SetSecurityDescriptorDacl; int64_t LookupPrivilegeValueA; int64_t StartServiceCtrlDispatcherA; int64_t SetServiceStatus; int64_t RegisterServiceCtrlHandlerA; int64_t RegDeleteValueW; int64_t RegOpenKeyExW; int64_t RegQueryInfoKeyW; int64_t RegDeleteValueA; int64_t IsTextUnicode; int64_t RegQueryValueExW; int64_t RegSetValueExW; int64_t LookupAccountNameW; int64_t RegEnumValueW; int64_t CredEnumerateA; int64_t CredFree; };

struct hashes_18000197b {int64_t StrStrIA; int64_t StrStrIW; int64_t StrCmpIW; int64_t PathCombineA; int64_t PathCombineW; int64_t PathMatchSpecA; int64_t PathMatchSpecW; int64_t PathUnquoteSpacesW; int64_t StrTrimW; int64_t StrCmpNIA; int64_t StrStrW; };

struct hashes_180001997 {int64_t ShellExecuteW; int64_t SHGetFolderPathW; };

struct hashes_1800019b3 {int64_t GetUserProfileDirectoryW; };

struct hashes_180002343 {int64_t WTSQueryUserToken; int64_t WTSQuerySessionInformationW; int64_t WTSEnumerateSessionsW; int64_t WTSFreeMemory; };

struct hashes_180002a25 {int64_t InternetOpenA; int64_t InternetOpenUrlA; int64_t InternetCloseHandle; int64_t HttpQueryInfoA; int64_t InternetReadFile; int64_t InternetSetOptionA; int64_t InternetQueryOptionA; int64_t InternetConnectA; int64_t HttpOpenRequestA; int64_t HttpSendRequestA; int64_t InternetCrackUrlA; int64_t InternetWriteFile; int64_t InternetGetLastResponseInfoA; int64_t InternetSetStatusCallback; int64_t HttpQueryInfoW; int64_t HttpAddRequestHeadersA; int64_t InternetGetCookieA; int64_t InternetGetCookieExA; int64_t InternetQueryOptionW; int64_t DeleteUrlCacheEntryW; int64_t GetUrlCacheEntryInfoW; };

struct hashes_180002a41 {int64_t ObtainUserAgentString; };

struct hashes_18000a3c1 {int64_t CryptDecodeObjectEx; int64_t CryptImportPublicKeyInfo; int64_t CryptUnprotectData; };

struct hashes_180001080 {int64_t LoadLibraryA; int64_t LoadLibraryW; int64_t FreeLibrary; int64_t GetProcAddress; int64_t GetModuleHandleA; int64_t GetModuleHandleW; int64_t CreateToolhelp32Snapshot; int64_t Module32First; int64_t Module32Next; int64_t WriteProcessMemory; int64_t OpenProcess; int64_t VirtualFreeEx; int64_t WaitForSingleObject; int64_t CloseHandle; int64_t LocalFree; int64_t CreateProcessW; int64_t ReadProcessMemory; int64_t Process32First; int64_t Process32Next; int64_t Process32FirstW; int64_t Process32NextW; int64_t CreateProcessAsUserW; int64_t VirtualAllocEx; int64_t VirtualAlloc; int64_t VirtualFree; int64_t OpenThread; int64_t Wow64DisableWow64FsRedirection; int64_t Wow64EnableWow64FsRedirection; int64_t GetVolumeInformationW; int64_t IsWow64Process; int64_t CreateThread; int64_t CreateFileW; int64_t CreateFileA; int64_t FindClose; int64_t GetFileAttributesW; int64_t SetFilePointer; int64_t WriteFile; int64_t ReadFile; int64_t CreateMutexA; int64_t ReleaseMutex; int64_t FindResourceA; int64_t FindResourceW; int64_t SizeofResource; int64_t LoadResource; int64_t GetTickCount64; int64_t ExpandEnvironmentStringsW; int64_t GetThreadContext; int64_t SetLastError; int64_t GetComputerNameW; int64_t Sleep; int64_t SleepEx; int64_t OpenEventA; int64_t SetEvent; int64_t CreateEventA; int64_t TerminateThread; int64_t QueryFullProcessImageNameW; int64_t CreateNamedPipeA; int64_t ConnectNamedPipe; int64_t GetLocalTime; int64_t ExitProcess; int64_t GetEnvironmentVariableW; int64_t GetExitCodeThread; int64_t GetFileSize; int64_t VirtualProtect; int64_t VirtualProtectEx; int64_t unk_4996c616; int64_t CreateRemoteThread; int64_t SetEnvironmentVariableW; int64_t ResumeThread; int64_t TerminateProcess; int64_t unk_33439cf0; int64_t DeleteFileW; int64_t CopyFileW; int64_t AllocConsole; int64_t SetConsoleCtrlHandler; int64_t GetModuleFileNameW; int64_t GetCurrentProcess; int64_t CreatePipe; int64_t GetExitCodeProcess; int64_t GetCommandLineW; int64_t DuplicateHandle; };

struct hashes_18000109b {int64_t SetFileSecurityW; int64_t AdjustTokenPrivileges; int64_t SetEntriesInAclA; int64_t AllocateAndInitializeSid; int64_t FreeSid; int64_t RegOpenKeyExA; int64_t RegQueryValueExA; int64_t RegCloseKey; int64_t ConvertSidToStringSidA; int64_t ConvertSidToStringSidW; int64_t RegCreateKeyA; int64_t RegSetValueExA; int64_t RegLoadKeyW; int64_t RegUnLoadKeyW; int64_t OpenSCManagerW; int64_t CreateServiceW; int64_t StartServiceW; int64_t DeleteService; int64_t CloseServiceHandle; int64_t CryptAcquireContextA; int64_t CryptCreateHash; int64_t CryptHashData; int64_t CryptVerifySignatureA; int64_t CryptReleaseContext; int64_t CryptDestroyKey; int64_t CryptDestroyHash; int64_t CryptDeriveKey; int64_t CryptSetKeyParam; int64_t CryptEncrypt; int64_t CryptDecrypt; int64_t CryptGetHashParam; int64_t EqualSid; int64_t LookupAccountSidW; int64_t OpenProcessToken; int64_t GetTokenInformation; int64_t OpenThreadToken; int64_t GetSidSubAuthorityCount; int64_t GetSidSubAuthority; int64_t ConvertStringSecurityDescriptorToSecurityDescriptorW; int64_t GetSecurityDescriptorSacl; int64_t SetSecurityInfo; int64_t InitializeSecurityDescriptor; int64_t SetSecurityDescriptorDacl; int64_t LookupPrivilegeValueA; int64_t StartServiceCtrlDispatcherA; int64_t SetServiceStatus; int64_t RegisterServiceCtrlHandlerA; int64_t RegDeleteValueW; int64_t RegOpenKeyExW; int64_t RegQueryInfoKeyW; int64_t RegDeleteValueA; int64_t IsTextUnicode; int64_t RegQueryValueExW; int64_t RegSetValueExW; int64_t LookupAccountNameW; int64_t RegEnumValueW; int64_t CredEnumerateA; int64_t CredFree; };

This script can be viewed in its entirety here.

We then imported these structures into Binary Ninja by right-clicking in the Types menu and clicking on Create Types from C Source...:

We then applied each structure to their function table pointer within the database. Here is an example function table with a structure applied:

Decrypting String Tables

With the dynamic function tables resolved, we were able to analyze the string table decryption functionality. Qakbot decrypts string tables using AES-256 in CBC mode where the key is derived by hashing a hard-coded value with SHA256. The derived key is used to decrypt an XOR key that is used to decrypt the string table in its entirety.

We use the same visit technique to generically identify all string table decryption function call locations to gather necessary attributes:

def visitor(_a, inst, _c, _d):

if isinstance(inst, commonil.Localcall):

if len(inst.params) == 7:

if len(list(inst.function.instructions)) == 1:

xor_key, ct = get_xor_key_and_ct(inst)

decrypted_str_table = xor_byte_data(ct, xor_key)

markup_str_as_comments(decrypted_str_table, inst)

return False

def markup_string_tables(bv):

key = None

for inst in bv.hlil_instructions:

inst.visit(visitor)

return key

Here we call get_xor_key_and_ct which extracts all data related to the string table from our identified function call:

def get_xor_key_and_ct(inst):

#mw_decrypt_data(&data_180027240, 0x5ab, &data_1800271a0, 0x90,\

# &data_180027150, 0x47, arg1)

tokens = inst.tokens

ct_addr = tokens[3].value

ct_len = tokens[5].value

ct = bv.read(ct_addr, ct_len)

iv_xor_ct_data_addr = tokens[8].value

iv_xor_ct_data_len = tokens[10].value

iv_xor_ct_data = bv.read(iv_xor_ct_data_addr, iv_xor_ct_data_len)

aes_key_data_addr = tokens[13].value

aes_key_data_len = tokens[15].value

aes_key_data = bv.read(aes_key_data_addr, aes_key_data_len)

xor_key = decrypt_aes(aes_key_data, iv_xor_ct_data)

return xor_key, ct

This includes iv_xor_ct_data which contains the following structure:

struct iv_xor_ct_data {

BYTE aes_iv[16];

BYTE encrypted_xor_key[];

};

This structure contains an initialization vector followed by an encrypted XOR key that is used to decrypt the string table. This structure along with all other required data is then passed to decrypt_aes that hashes aes_key_data with SHA256 and uses this as an AES-256 key to decrypt the XOR key:

def decrypt_aes(aes_key_data, iv_xor_ct_data):

h = SHA256.new()

h.update(aes_key_data)

aes256key = h.digest()

cipher = AES.new(aes256key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv_xor_ct_data[:16])

xor_key_ct = iv_xor_ct_data[16:]

xor_key = unpad(cipher.decrypt(xor_key_ct), AES.block_size)

return xor_key

The decrypted XOR key and the string table ciphertext are then returned from get_xor_key_and_ct as shown above. The XOR key is then used to decrypt the ciphertext within our visitor function:

def visitor(_a, inst, _c, _d):

if isinstance(inst, commonil.Localcall):

if len(inst.params) == 7:

if len(list(inst.function.instructions)) == 1:

xor_key, ct = get_xor_key_and_ct(inst)

decrypted_str_table = xor_byte_data(ct, xor_key)

markup_str_as_comments(decrypted_str_table, inst)

return False

Whenever a string is required throughout the execution of Qakbot, a string table decryption function is called and an offset to access a string within the table is provided. We can therefore enumerate all calls to each string table decryption function and identify these offsets and markup each call site with each decrypted string. This is done in the markup_str_as_comments function.

def markup_str_as_comments(decrypted_str_table, inst):

rstr = {}

for callsite in inst.function.source_function.caller_sites:

#print(F"Found call site: {callsite.address:08X}")

str_offset = get_str_offsets(callsite)

dec_str = decrypted_str_table[str_offset:].split(b"\x00")[0]

First, we enumerate all call sites from our generically identified instruction using inst.function.source_function.caller_sites. We then acquire each string offset within the decrypted string table using get_str_offsets:

def get_str_offsets(call_site):

#Get first call within nested operands, does not account for nested

#calls, but we haven't seen those.

rcall = recurse_get_call(call_site.hlil)

#Get first constant within operands of call

rconst = recurse_get_const(rcall)

if rconst:

return rconst.value.value

else:

return None

Here we had the unique problem of identifying each call associated with the callsite and extracting the offset (a constant) from the call. These calls differed in shapes and sizes in the HLIL, so we decided to recursively acquire the first call made at a call site and recursively acquire the constant when a call was found:

def recurse_get_call(instr):

# Base case: If the instruction is a call, return it

if instr.operation == HighLevelILOperation.HLIL_CALL:

return instr

# If the instruction has operands, recursively search within them

if hasattr(instr, 'operands'):

for operand in instr.operands:

if isinstance(operand, HighLevelILInstruction):

result = recurse_get_call(operand)

if result is not None:

return result

# If no call is found in this instruction or its operands

return None

def recurse_get_const(instr):

# Base case: If the instruction is a constant, return it

if instr.operation == HighLevelILOperation.HLIL_CONST:

return instr

# If the instruction has operands, recursively search within them

if hasattr(instr, 'operands'):

for operand in instr.operands:

if isinstance(operand, HighLevelILInstruction):

result = recurse_get_const(operand)

if result is not None:

return result

elif isinstance(operand, list):

for op in operand:

result = recurse_get_const(op)

if result is not None:

return result

return None

We were actually able to get Sidekick to help us with this by asking us how we could do this. Very cool!

Once the target offset is acquired, we are able to get the decrypted string from its table using: dec_str = decrypted_str_table[str_offset:].split(b"\x00")[0]. Each decrypted string is then marked at each callsite by adding it as a comment:

rstr["0x%x" % callsite.address] = dec_str.decode('ascii')

bv.set_comment_at(callsite.address, dec_str)

This allows us to see what decrypted string is being used where throughout the Binary Ninja database.

Recovering C2 and Campaign Info

Qakbot uses a specific string within these decrypted string tables as a SHA256 input with the result being used as a AES-256 key to decrypt its C2 server and campaign information (e.g., ewW300ns6&6HyygkKzfVVCJHq210vQLq7*uCNorQns). While enumerating string decryption callsites, we have additional checks for callsites that match the functions which process these strings and decrypt the data that we’re interested in:

#While we're enumerating all callsites, we should check them for the

#strings that are being used to decrypt the campaign info and C2

campaign_info = enum_callsite_for_campaign_func(callsite, dec_str)

if campaign_info:

print(campaign_info)

c2_info = enum_callsite_for_c2_func(callsite, dec_str)

if c2_info:

print(c2_info)

These functions use the same techniques described above to enumerate the callsite functions using heuristics and extracting the required parameters to recover required attributes. The first being campaign info:

def enum_callsite_for_campaign_func(inst, dec_str):

insts = list(inst.function.hlil.instructions)

campaign_info = None

if len(insts) > 5:

#Fingerprint with surrounding instruction types and number of basic blocks.

if(type(insts[4]) == HighLevelILVarInit

and type(insts[4].operands[1]) == HighLevelILCall

and type(insts[5]) == HighLevelILVarInit

and type(insts[6]) == HighLevelILIf and

len(inst.function.basic_blocks) == 5):

print(F"Found call to campaign info decryption function: {inst.address:08X}")

#uint32_t ct_len = zx.d(ct_len)

iv_ct_len_addr = insts[1].tokens[7].value

#WORD from aquired address for ciphertext length

iv_ct_len = (struct.unpack("H", bv.read(iv_ct_len_addr, 2))[0])

iv_ct_addr = insts[4].tokens[8].value

#Read ciphertext and IV from this address

iv_ct = bv.read(iv_ct_addr, iv_ct_len)

aes_key_data = dec_str

campaign_info = parse_campaign_info(decrypt_config_aes(aes_key_data, iv_ct))

#Need to get this as the decrypted string from the call site

return campaign_info

Here the callsite function for processing campaign ciphertext information contains the AES IV/ciphertext address and the length of this data (in the same format as the encrypted string table data). We use this information to recover the AES IV and ciphertext with bv.read. We then decrypt the campaign info by hashing the decrypted string with SHA256 as the AES-256 key in the decrypt_config_aes function. The decryped campaign info is then parsed with the parse_campaign_info function:

def parse_campaign_info(info_blob):

#Skip over SHA256 of config

info = info_blob[32:]

s_info = info.split(b"\r\n")

campaign_info = {}

for cinfo in info.split(b"\r\n"):

if b"10=" in cinfo:

campaign_info['campaign_id'] = cinfo.split(b"=")[1].decode('ascii')

elif b"3=" in cinfo:

campaign_info['timestamp'] = cinfo.split(b"=")[1].decode('ascii')

return campaign_info

This is followed by a similar technique to recover and decrypt the C2 information:

def enum_callsite_for_c2_func(inst, dec_str):

insts = list(inst.function.hlil.instructions)

c2_info = None

#Fingerprint with surrounding instructions, we can probably improve

#on this.

if(len(insts) > 20 and type(insts[17]) == HighLevelILVarInit and

len(inst.function.basic_blocks) == 46):

print(F"Found call to C2 decryption function: {inst.address:08X}")

#uint32_t ct_len = zx.d(ct_len)

iv_ct_len_addr = insts[14].tokens[7].value

#WORD from aquired address for ciphertext length

iv_ct_len = (struct.unpack("H", bv.read(iv_ct_len_addr, 2))[0])

iv_ct_addr = insts[17].tokens[8].value

#Read ciphertext and IV from this address

iv_ct = bv.read(iv_ct_addr, iv_ct_len)

aes_key_data = dec_str

return parse_c2_info(decrypt_config_aes(aes_key_data, iv_ct))

Then parse the decrypted C2 information:

def parse_c2_info(c2_info_blob):

c2_info = []

#Skip over C2 config SHA256 and boolean

info = c2_info_blob[32:]

#Each C2 entry is 8 bytes

num_entries = len(info) // 8

for i in range(0, num_entries):

ip_port = info[i*8:i*8+8]

ip = socket.inet_ntoa(ip_port[1:5])

port = struct.unpack(">H", ip_port[5:5+2])[0]

c2_info.append({"IP": ip, "Port": port})

return c2_info

This results in the recovery of the Qakbot campaign and C2 information from the binary:

python3 decrypt_aes.py qakbot-64-bit/dll/780be7a70ce3567ef268f6c768fc5a3d2510310c603bf481ebffd65e4fe95ff3/sc-tmp/third_carved_dll.bin

Found call to campaign info decryption function: 180003313

{'campaign_id': 'tchk06', 'timestamp': '1702463600'}

Found call to C2 decryption function: 180006175

[{'IP': '45[.]138[.]74[.]191', 'Port': 443}, {'IP': '65[.]108[.]218[.]24', 'Port': 443}]

The full script for performing string table markups and extracting this information can be found here. From a malware analysis/triage perspective, with recovered strings, APIs, C2 and campaign information, the next step would be to reverse engineer the remaining functionality of Qakbot using Binary Ninja. We have, however, automated the recovery of obfuscated information using techniques that work across multiple samples in order to assist during the reverse engineering process. The extracted indicators of compromise can also be used to identify further infections within an environment and block outbound communcations to the botnet C2 infrastructure. Campaign information can be used to track distribution campaigns.

Conclusion

Binary Ninja provides a robust API for interacting with its database and syntatic representations of code. These APIs and BNILs can assist in extracting information that may be difficult to acquire directly from dissembled code, and provides helper functions for navigating its intermediate representations quickly. Tools like Sidekick provide a means of leveraging AI models to assist during the reverse engineering process, and we are excited about the prospect of leveraging them further within our workflows.

Acknowledgements & References

- Huge shoutout to Jordan from Vector35 @psifertex for hopping on our streams multiple times during his weekends to help us with our scripting and Binary Ninja use.

- Huge shoutout to Sergei from OALabs @herrcore for helping us throughout this stream series with various aspects.

- Tracking 15 Years of Qakbot Development - used as a reference when decrypting string tables. Thanks ZScaler team (shoutz ThreatLabz and BSG)!

- https://malcat.fr/blog/writing-a-qakbot-50-config-extractor-with-malcat/ - used as a reference when figuring out the campaign info and C2 data formats. Thanks Malcat team!

Samples

- 780be7a70ce3567ef268f6c768fc5a3d2510310c603bf481ebffd65e4fe95ff3

- 12094a47a9659b1c2f7c5b36e21d2b0145c9e7b2e79845a437508efa96e5f305

All the best,

The Invoke RE Team